Maratona dles Dolomites

One day a year in the normally sleepy Ladin valleys of Italy’s far north, a gunshot sends more than 9,000 riders climbing out of the darkness, just before dawn breaks over the surrounding limestone peaks.

Throughout the huge peloton, the atmosphere is electric. At the front, the pace is almost frightening. Bands line the roadside. At some turns the fans are five or six deep behind the hoardings. It’s almost impossible to get an entry—more than 30,000 apply for the lottery—and in the excitement of it all during those first few kilometers, it’s all too easy to forget just what the hell you’ve signed yourself up for.

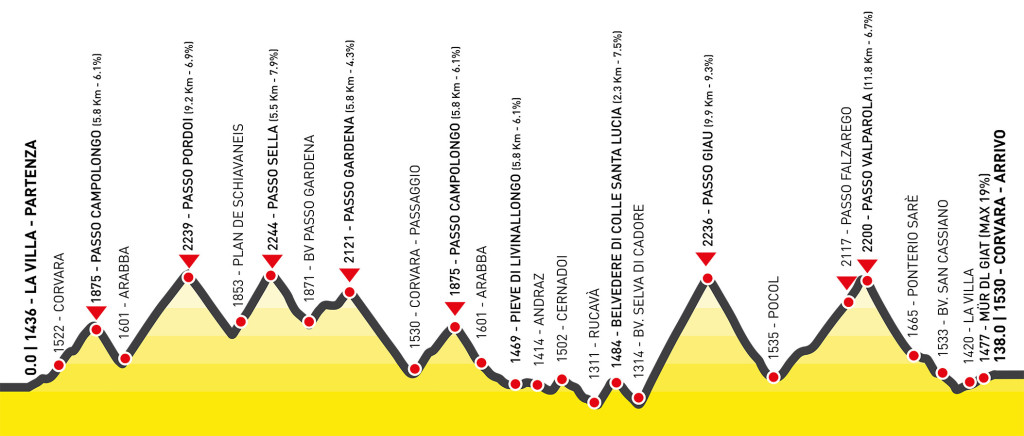

This is the Maratona dles Dolomites, the queen of all gran fondos. It’s grueling, beautiful, fun, overwhelming, unforgettable. It’s breathtaking, both figuratively and literally. And for an amateur rider, there’s simply nothing else like it. In fact, the scale of it is probably enough to shock a lot of lower-level pros. There are three courses, none of them exactly easy. The shortest looks benign enough at first glance, just 55 kilometers. It still manages to pack in almost 1,800 meters of climbing. The medium route takes 106 kilometers, with 3,090 meters of elevation. And then there’s the Maratona proper, 138 kilometers of extraordinary, excruciating riding that climbs just short of 4,200 meters (13,780 feet).

MARATONA’S SEVEN CLIMBS

- Passo di Campolongo (5.8 km at 6.1%)

- Passo Pordoi (9.2 km at 6.9%)

- Passo di Sella (5.5 km at 7.9%)

- Passo di Gardena (5.8 km at 4.3%)

- Passo di Campolongo (5.8 km at 6.1%, second crossing)

- Passo di Giau (9.9 km at 9.3%)

- Passo di Falzárego/Valparola (11.5 km at 5.8%)

Unlike the vast majority of such events, the Maratona isn’t designed to be simply a suffer-fest. It’s a celebration of cycling, of the Dolomites and of the area’s unique culture. It’s incredibly inclusive. Turn up and enjoy yourself, and you’ll fit right in.

The race’s patron, Michil Costa, is what the Italians call a personaggio, a character. His goal is to get people to connect with nature, to contemplate their place in it, and to appreciate not only its fragile beauty but also what that beauty can do for our own fragilities. Riding here might be tough on the legs, but it does wonders for a stressed-out mind.

The landscape of the Dolomites is so important and so inspiring that it’s protected by Unesco, and every year the Maratona has an environment-related theme. The official jerseys have a fourth pocket, on the side, for your trash. But because there will always be idiots who think it’s okay to toss their gel wrappers once they’re done, the day after the race several hundred volunteers walk the entire route picking up the pieces to make sure it’s left spotless. From start to finish, this is a race that’s done right.

And then there’s the history. It’s not an overstatement to say that without roads like these, there would be no Grand Tours—or at least not the kind worth watching. The Pyrénées, the Alps and the Dolomites are the backdrops for some of cycling’s most memorable moments and the theatres in which the sport’s greatest protagonists have given their most enthralling performances. The Dolomites have given birth to the stars of the Giro d’Italia, where its legends are written. For fans of Coppi, Bartali, Merckx or Pantani, the Maratona will be less a race than it is a pilgrimage.

These mountains are full of such stories. The Passo Pordoi has hosted the Giro 37 times since 1940, and seen generations of stars shine on its slopes from Bartali, Coppi and Hugo Koblet to Laurent Fignon, Claudio Chiappucci and Miguel Induráin. The Ladin valleys, the looming majesty of the Marmolada, and the jagged, craggy faces of the Gruppo del Sella are as woven into the history of cycling as those winding, breathtaking roads are entwined in the mountains.

The Passo di Giau is no less famous, or infamous, depending on how much you like long, 10-percent climbs. It’s set the Giro alight on many occasions, most recently in 2012 when Joaquim Rodríguez and Ryder Hesjedal were battling for the maglia rosa. Every summer, it’s also the centerpiece of the Maratona’s longest course. It’s been described as a sting in the race’s tail. Whoever started that rumor is a master in understatement. It’s the penultimate climb of the day, and generally the one that riders are most worried about.

The average gradient is around 9.5 percent, kicking now and then up to 15 percent, and it rises more than 920 meters (just over 3,000 feet) in a little under 10 kilometers. For the serious climber, it’s a chance to have some fun. The gradient is steady and the surface good. But arrive at it underprepared or overcooked, and it’s like taking a shot to the chest. At the top, you’ll be 2,236 meters (7,336 feet) above sea level, surrounded by snow and rock and little else.

You’ll also be staring at an incredibly fun, and fast, descent into Pocol, one that’s made all the more entertaining, and perhaps a little sketchier, by the fact that you’re hurtling down the mountain with so many other cyclists. And after that? There’s just the small matter of the 11.5 kilometers to the top of Falzárego and the Passo Valparola, in the tracks of Coppi and Bartali, and not so terribly far away from a well-earned beer and bowl of pasta at the finish.

Words by: Colin O’Brien, Rome, Italy. @ColliOBrien

Published in Peloton Magazine, March 2015.