Power Based Training: What Every Cyclist Should Know

Power is the only objective metric you can use to train with. Other metrics — distance, heart rate, RPE — are subjective. This isn’t newfound knowledge. Most cyclists know this, but there are far fewer cyclists who have spent the time to really get it. So why is having more than a baseline understanding of power important; why does objectivity in training even matter; and what exactly does power have to do with getting faster?

At the heart of it, training with power is pure efficiency. We all know those cyclists who periodically log long rides throughout the week. Their focus is miles, miles, miles. After months of what’s thought to be structured training, those same athletes often get frustrated when they see little-to-no improvement in their functional threshold power (FTP). This isn’t surprising.

The habitually ignored truth is that without power your training cannot have the kind of structure optimal for fitness gains. You need power, an exclusively objective metric, to have true structure. True structure allows for progressive, properly timed and systematic training stress. That key mix of variables is how you get faster.

So what if your training lacks structure? As our Head Coach Chad Timmerman would put it, you’re simply bike riding. That’s not a bad thing if your primary goal on the bike is to have fun. If, however, fun is slightly lower on the list — like say under winning, PRs and a host of other specific fitness aspirations — then a lack of structure is an issue you should address.

Pro cyclists, riders who almost always prioritize winning above having fun, understood the potential of power-based training decades ago. Andrew Coggan explains the history more in depth, but it’s basically this: ever since the the mid-to-late-1980s when it became possible to measure a cyclist’s power with the development of the SRM, pros have been doing it. This isn’t just because pros are data snobs. The most forward-thinking athletes and their coaches understood (and still understand) that the true gift and genius of training with power is in the ability to precisely measure performance. Measure being the key here.

What is Power?

Let’s take a couple steps back and address what power is exactly. In the context of cycling, power is a measurement of how much work you’re doing on the bike. To get more specific, power = force x speed. So it’s not only how hard you’re pushing on the pedals, but how quickly you’re turning them (i.e. your cadence) that determines your power. Power is said to be objective because 300 watts, for instance, will always be 300 watts. You can’t use that same clear-cut logic with other subjective metrics.

Take milage for example. If you rode 10 miles one day and 10 miles the day after that, riding the exact same distance does not guarantee your efforts on both days were equivalent. Just as riding 15 miles one day and 10 miles the next day does not guarantee you made more of an effort on the day you rode 15 miles. On the day you rode fewer miles you could have been on an uphill course going against some major headwind, whereas the day you rode more miles it could have been on a flat stretch of road without a hint of gust. When you consider the conditions it’s obvious you would have worked much harder on the day you rode fewer miles.

This example underscores a couple critical training principles: More is not always more, just as less is not always less; and the only confident way an athlete can legitimately compare, contrast and ultimately measure their effort from workout to workout is by looking at their power output.

How to Use Power to Optimize Your Training

If you want to get faster, training your body at the right intensity at the right time is paramount. Executing on this is not as simple as doing a gut check and asking yourself what kind of workout you’re up to doing that day. (If only it were that easy.) There’s a lot more to consider when deciding how and when certain training stress is applied. Your current level of fitness and the specific event for which you’re preparing for are the two biggest variables that influence the amount of training stress you need to reach your cycling goals.

If a cyclist who is new to training with power does not consider these variables, there are a couple unproductive situations that commonly occur. The first is that they do too much too early and they burnout. The second is that they don’t train at the correct intensity and their training is either too easy or too hard, i.e. not efficient and, therefore, not as effective as it could be.

The good news is that these situations are avoidable when you structure your workouts with power zones based off of a reliable estimate of your threshold power — the highest power you can consistently maintain for an hour without fatiguing. This is the critical reason the first workout TrainerRoad athletes do is a Ramp Test, designed to find their Functional Threshold Power (FTP). The results of their FTP test are used to custom calibrate the intensity of all the workouts they do on TrainerRoad.

How to Determine Your Functional Threshold Power

There are a number of ways you can get an idea of what your threshold power is, including looking at a power file, analyzing training data from your power-meter software and enduring a TT assessment. Some methods will provide you with a more precise idea of what your threshold is, whereas others will give you more of a ballpark estimate. To keep things simple, let’s focus on one of the most popular ways to determine your FTP: a 20-minute time trial.

A 20-minute TT can be performed outdoors or indoors on the trainer. While it goes without saying, the less variables you have when testing will produce more reliable and repeatable test results. This is why testing indoors is favored. Doing so means you can eliminate road conditions, traffic, weather and all of those other things that are out of your control when riding outdoors.

If you don’t have the option to test indoors, then it’s critical you find a uniform, flat stretch of road where you can put out power consistently for 20 minutes without interruption. You’ll also want to try to replicate weather conditions whenever possible. Once you’ve nailed down your assessment environment, follow this simple procedure:

• Warm up for about 20 minutes. Don’t soft pedal the whole time, mix in some bursts of intensity

• Do your 20-minute all-out time trial effort

• Cool down for 10-15 minutes

After your time trial, calculate your average power and reduce it by 5%. So, for example, if your average power for your 20-minute effort was 300 watts, calculate 300x.05 = 15, then 300-15= 285, which will be your FTP. You could also simply do 300x.95 to get your answer.

The reason you reduce your average power by 5 percent is because your max 20-minute effort is going to be a little bit higher than your max 60-minute effort. This is an established protocol that is used to roughly equate most closely to your true FTP, aka your 60-minute power.

How to Determine Your Power Zones

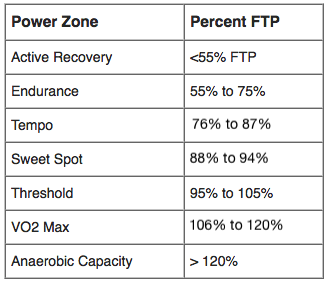

Once you’ve determined your FTP, you’re now in a position to start structuring your workouts based off of power zones. Training intensity is commonly defined by seven power zones. Each power zone is defined by a percentage of your FTP and a specific training adaptation.

With the information provided in the above table, create your own table that defines your training power zones. To do this, list out each of the seven power zones in a column and in the column directly to its right insert the percentage of your FTP according to each defined power zone. So, if you determined your FTP was 300, for the first row in your table you will have to calculate 300x.55 = to determine your Active Recovery power zone is anything under 165 watts.

This is the beauty of knowing what your FTP is! You now have the ability to customize workouts to your specific fitness level and develop true structure in your training so that you’re experiencing different types of training stress at the right amount and time for the event you’re preparing for. There are two words that should define your training moving forward: effective and efficient. There are a handful of cyclists out there who just focus on that first descriptor. We’re just as concerned about the latter.

For the vast majority of cyclists, structure is everything. Sure you can get faster without having structure — but that’s not the point. Time is. Most of us don’t have the time (we’re talking 20+ hours a week) to devote to the traditional way of training, which is to get out and log a ton of miles. That means the time we do have available to train, especially during our busy work-week days, must be two things: high quality and goal oriented. Structure makes this possible. It’s as simple as that.

What You Need to Start Training with Power

Training with power has the reputation for being a bit complicated (we hope our discussion above helped simplify things) and, most of all, expensive. Most cyclists assume if they want to start training with power, they first need to invest several hundred dollars into getting a power meter. This is no longer the case with VirtualPower .

.

To start getting the benefits of structured, power-based training, all you need is a speed sensor and a supported trainer. The upside is that VirtualPower supports nearly every trainer on the market. The speed sensor is then used to connect TrainerRoad with your trainer’s unique power curve to give you power data in real time. And that’s it — those two things are all you need to start training indoors with power.

** Our default testing format to estimate an athlete’s FTP was changed to the TrainerRoad Ramp Test since this post was published

Want to learn more about the easiest and most cost-effective way to train with power? Have a look at our VirtualPower page.

For more answers to your cycling training questions, listen to The Ask A Cycling Coach Podcast — the only podcast dedicated to making you a faster cyclist. New episodes are released weekly.