Criterium Race Analysis: Attacking vs. Patrolling

We put GoPros on two of our strongest riders, Dave and Pete, giving you an inside look at our local Tuesday Night Worlds criterium. I sit down with the riders and analyze the two different ways they approached the race.

If you like the race commentary, leave a comment on the video letting us know your biggest takeaway, and subscribe to the TrainerRoad YouTube channel. As long as we know you like these videos, we’ll continue to do more!

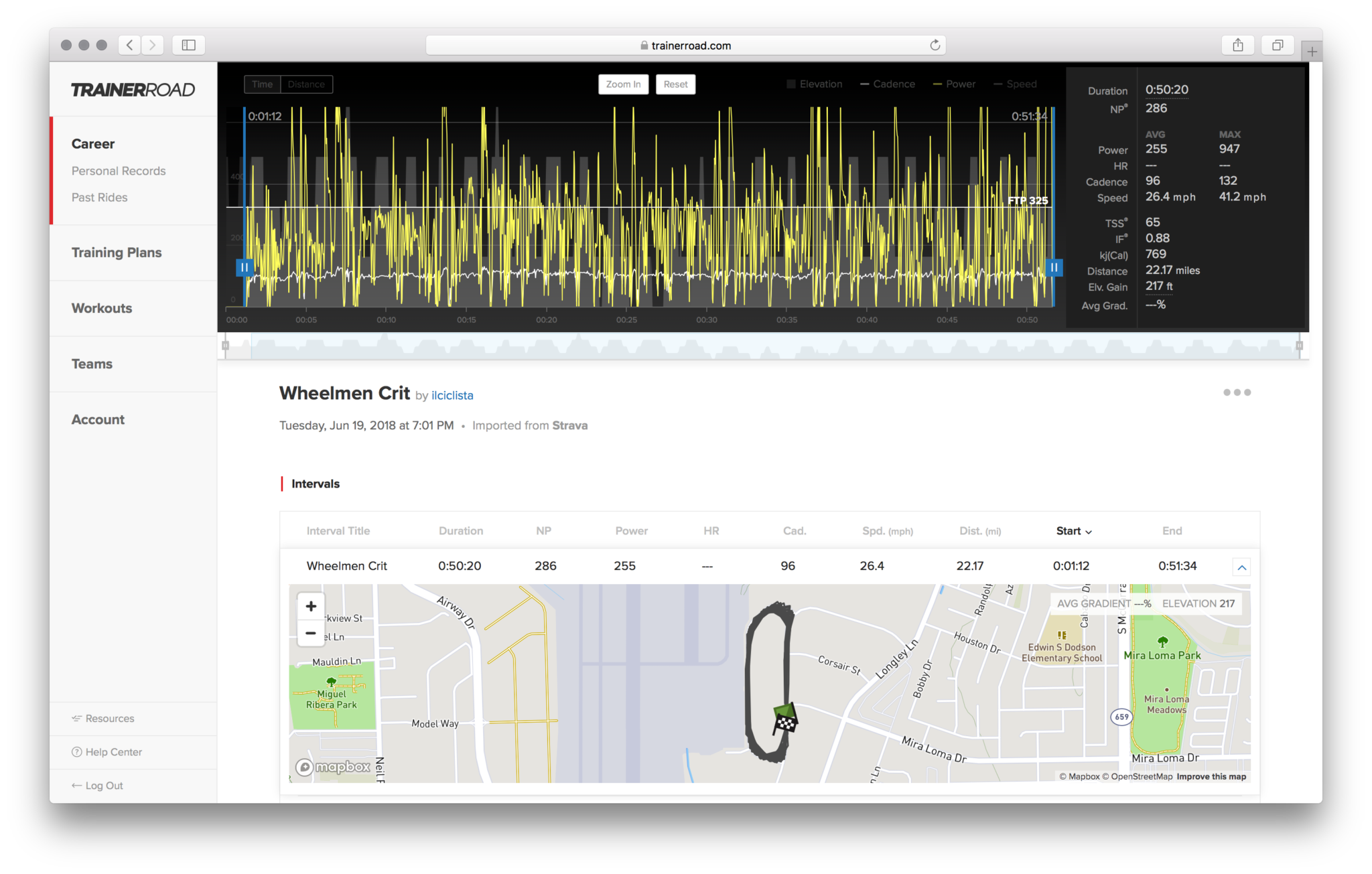

Dave’s Approach: Patrolling

Analyze Dave’s race for yourself using Performance Analytics

Patrolling’s reactive nature is often misunderstood as a passive approach to bike racing. When properly patrolling a race, there is a massive energy and psychological cost. Dave does a great job of patrolling in this race due to his stellar fitness, broad experience, and knowledge of his competition.

Dave’s fitness profile lends itself toward late race attacks rather than sprint finishes, so piggybacking on a decisive move that distances himself from the main sprinters gives himself the best shot at a victory. The fitness needed to endure this type of racing focuses on repeatability, with attacks and reactions going briefly into anaerobic territory and time in between attacks and responses is often spent below threshold while still maintaining a good pace.

Patrolling requires you to be confident in your ability to ride at the front of the pack for the duration of the race, but your goal is not to give the pack a free ride. Instead, you are waiting in the best position possible to react to the decisive move. An extra perk of patrolling at the front is that it allows you to influence the pace of the race at times, however, this usually means you are sacrificing some of the drafting benefits you get from sitting deeper in the pack.

Dave cleverly placed himself toward the front and even threw out a few attacks of his own, but his focus during these attacks was on the response it earned from the pack. At times you’ll need to animate the race just enough to gather information on the current status of your competitors. The real trick with this is to make your competitors believe these attacks are genuine threats so you can get a reaction, but doing so without tiring yourself out excessively.

Other than having the fitness to ride toward the front, throw strategic attacks and react to the decisive move, the most difficult part of patrolling is accurately discerning which move is the decisive one to follow.

If you don’t know your competition, you’ll likely end up chasing every move just in case it ends up being decisive. This rarely results in a good finish.

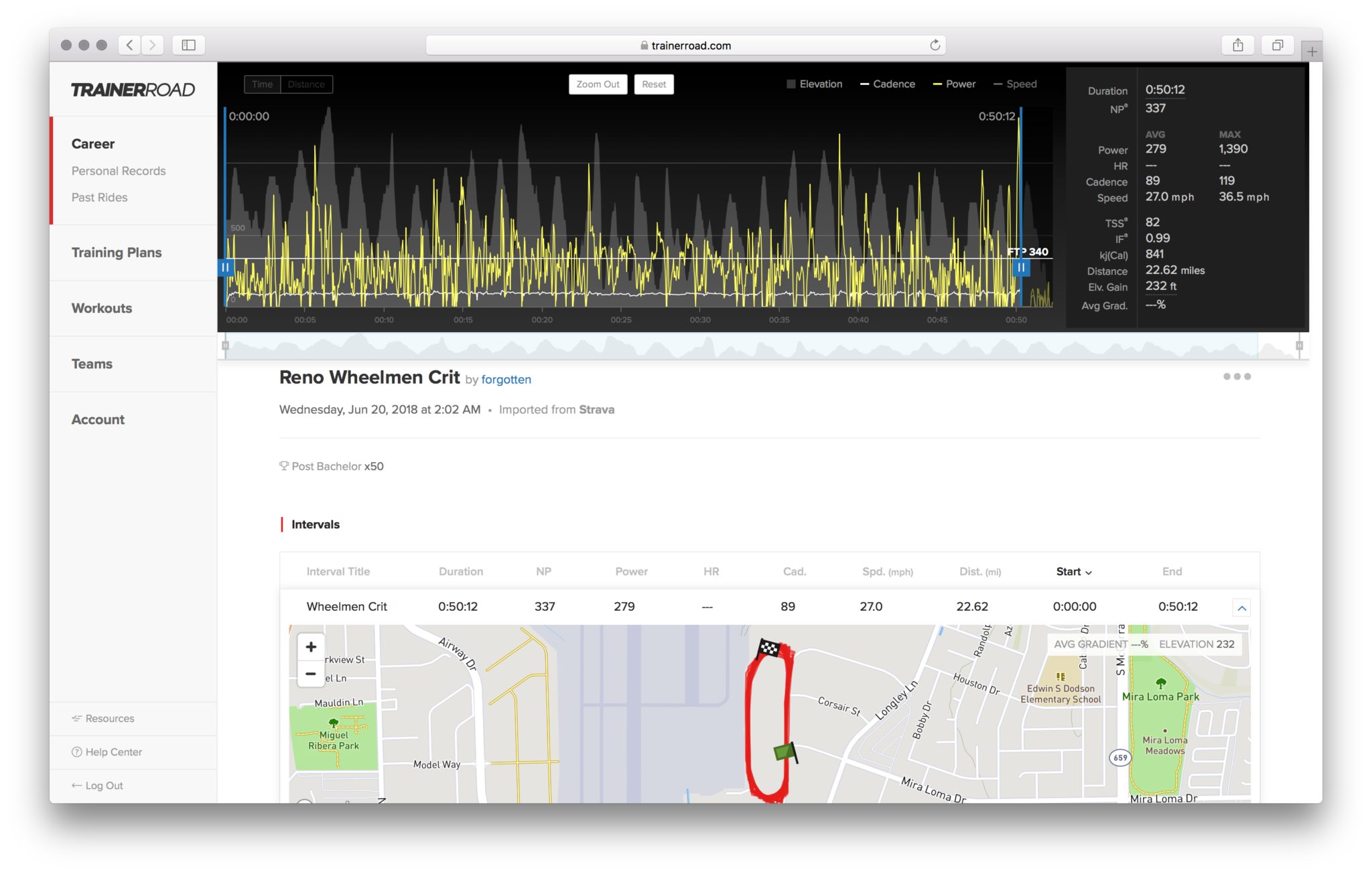

Pete’s Approach: Attacking

Analyze Pete’s race for yourself using Performance Analytics

Anybody can attack, but making an attack stick is a different task altogether. Pete knows that his fitness profile allows him to be competitive in a sprint, but a more likely victory comes from a long attack early on in the race.

Attacking racers commonly get caught in the “thick of thin things” and lose sight of the main objective: get away, stay away. They prematurely judge an attack’s effectiveness from the immediate response from the pack, rapidly shutting down their attacks that don’t allow them to go solo or with their ideal breakaway companion. This results in a high number of minimally effective but maximally draining attacks, whereas fully committing to one quality attack will likely deliver greater success.

Pete is fully committed to his attacks in this race. He intelligently bases a lot of his moves on the pace of the pack and positions himself in such a manner to allow himself to maintain and build speed while the pack is slowing. Pete does this by dropping to the back of the decisive group after an attack, then swinging wide through corners to allow maximum momentum. This allows Pete to build enough speed by the time he passes the front of the group that most racers aren’t willing to work hard enough to latch onto his wheel.

But the most important part of Pete’s attacks come after the initial move. Rather than immediately looking back and choosing whether to stop attacking or not, Pete stays focused on his attack and doubles down. Pete has a high threshold and is fully committed to riding at or around that threshold for as long as needed to get a sufficient gap.

Once a significant gap has been established, Pete reassesses the situation. If there are breakmates with him that he considers threats, he instantly employs tactics such as letting them fill in gaps in the rotation or upsetting the rhythm of the group strategically to make those riders work harder. If he notices the pack working together and successfully catching them, he continues conservatively but keeps the pressure high, hoping the group may have lost interest or energy.

Conclusion

Neither of these approaches delivered the win in this race, but that doesn’t mean these were the wrong approaches to employ. Both racers performed admirably but were simply out-sprinted in the end. One of the main appeals of criterium racing is the chance to test different approaches and see what works. When the stars align, it equals a race win, but regardless of the result it delivers solid learning experiences and fitness gained that make you a faster cyclist.

For more cycling training knowledge, listen to the Ask a Cycling Coach — the only podcast dedicated to making you a faster cyclist. New episodes are released weekly.