The Syntace K.I.S. system of the Canyon Spectral CF 8 K.I.S. in test – A revolution in MTB steering dynamics?

Some inventions forever change the way we ride mountain bikes. Now, according to Canyon, the new K.I.S. system is meant to do just that, influencing both the steering dynamics of mountain bikes and the future direction of mountain biking. But what is it, how does it work, and above all, does it do what it says on the tin?

K.I.S. – short for keep it stable – is an invention of German component manufacturer Syntace, who isn’t afraid to try new ideas and approaches. For the time being, the system can be found exclusively on the Canyon Spectral CF 8 and Liteville 301 eMTB. In a nutshell, the K.I.S. mechanism consists of a spring that is connected to a cam ring on the fork’s steerer tube and an anchor point in the top tube. As you turn the bars away from the centre, the spring tensions, pulling the bars back into their original position. This is supposed to bring several advantages on the trail by improving the overall stability of the bike, both when riding in a straight line and when cornering, while at the same time mitigating understeer. Moreover, it’s supposed to delay fatigue on long descents by reducing the amount of input required from the rider. According to Canyon’s own statement, the system will have a similar impact on mountain biking as the dropper post and hydraulic disc brakes. But is this just a bold claim or will the K.I.S. system revolutionise the steering dynamics of mountain bikes?

Background and functioning of the steering mechanism

Before explaining how the K.I.S. system actually works, it makes sense to take a closer look at the basic function of the steering system of a bike. At first, you might think: “It’s not rocket science, is it? You just move the handlebars and the front wheel turns!”. Yes, sort of, but it’s a lot more complex than that. You just have to watch a bike race, no matter whether it’s XC, Downhill or the Tour de France, and you’ll notice that the riders tend to lean the bike into the corner rather than turning the bars, especially when riding at high speed.

Another effect that has a big influence on the steering behaviour of a bike is the trail of the fork, which varies depending on the fork offset as well as the head angle and wheel size. Simply put, the longer the trail, the more self-centering effect on the front wheel, which in turn gives the bike more stability. You can think of it like the wheel of a shopping trolley that is offset in relation to the axis of rotation and therefore aligns with the direction of travel of the trolley. All these effects influence the function of the K.I.S. system.

How the K.I.S. system works.

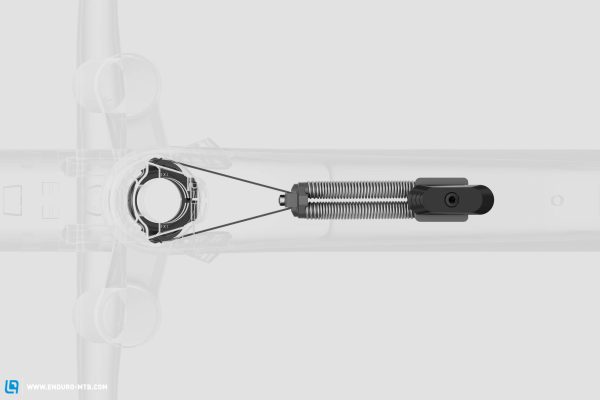

The basic principle of the K.I.S. system is pretty simple: a coil spring, which is attached to an oval cam ring on the steerer tube and an adjustable anchoring point in the top tube, gains tension every time you turn the handlebars. This pulls the bars back towards the centre. However, as usual, the devil’s in the detail.

Two straps connect the spring to an oval cam ring that, in turn, is bolted to the steerer tube. The arrangement of the straps and the spring determines the 0º position of the steering while the force required to turn the handlebars can be changed using different cam ring shapes. The spring system doesn’t employ any bearings, dampers or additional parts that require maintenance. In addition, it has no friction losses and only adds around 120 g to the overall system weight. According to the developers, the K.I.S. was put through the wringer and subjected to a million steering cycles in the lab. However, should you ever have a problem with the spring, you can get spares directly from Canyon. The spring rate is the same across all frame sizes but you can change the preload using the small sliding switch integrated into the top tube, which allows you to fine-tune the resistance to suit your weight, handlebar width and personal preferences. To set the preload, you have to loosen the 4 mm Allen bolt on the slider, set this to the desired position and tighten the bolt.

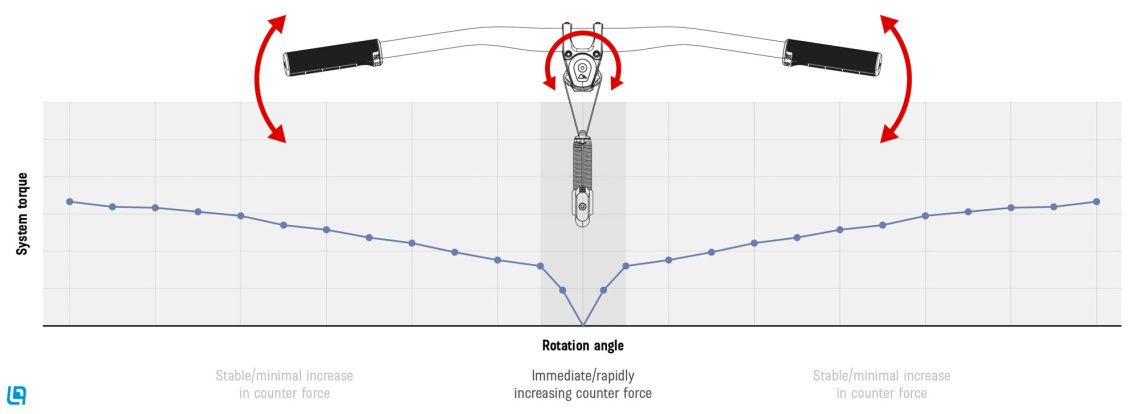

The diagram shows the amount of torque the K.I.S. system exerts on the handlebars with steering angles of up to 90°, both left and right. A mechanical stop limits the steering angle to 90º, thus preventing the spring from overstretching. While the diagram doesn’t show any absolute values, you can still see that the required force increases sharply around the middle. This keeps the handlebars firmly centred and creates a clearly-perceivable resistance as soon as you initiate the steering process. Since the resistance curve is particularly steep in the first phase, the forces required to turn the bars from, let’s say, 5° to 10°, are very high. And it doesn’t matter whether these forces are applied by the rider through the handlebars or by the irregularities of the ground, which means that the handlebars only move with stronger side impacts on the wheel. This is meant to stabilise the bike when riding in a straight line, for example when bombing down fast bike park trail section on rough terrain.

Due to the oval shape of the cam ring, the required force reduces the further the bars turn. As a result, you’ll require significantly less strength to spin the handlebars from 40° to 45° than from 5° to 10°, for example. This is intended to prevent you from having to wrestle the bike in narrow corners. However, when initiating the steering process, the lower spring force also makes it easier for side impacts on the wheel to move the handlebars.

The Canyon Spectral CF 8 K.I.S.

At first glance, it’s hard to tell apart the Canyon Spectral CF 8 K.I.S. from the conventional Spectral model without K.I.S. – which comes as no surprise, because they’re basically the same bike. Only the small tension regulator on the top tube gives away the Keep It Stable system. The Canyon Spectral CFR has already proven its all-round qualities in our latest trail bike test. The CF 8 relies on the same frame platform, but is made of a slightly heavier carbon and features a slightly cheaper spec. One important factor in this is that the CF 8 K.I.S. also shares the same fork as its standard counterpart, which has the same 44 mm offset, thus maintaining the same trail and, as a result, ensuring consistent steering behaviour.

The K.I.S. system is neatly integrated into the frame of the Canyon Spectral CF 8 K.I.S. and the only differences to the conventional Spectral are the slider of the spring mechanism in the top tube and the small hole on the side of the head tube, from which you can access the oval cam ring. Changing the preload is done quickly and easily – an Allen key is all you need. The adjustment range is big enough to notice a clear difference, but the system can’t be bypassed altogether – to do this, you’d have to remove it!

Test: The K.I.S. system in the Canyon Spectral CF 8 K.I.S. on the trail

When hitting the first few corners, the Canyon Spectral CF 8 K.I.S. feels a little unusual at first. We recommend starting off with the least preload, because even in the weakest setting, you can clearly feel the resistance. In the first few metres, you’ll feel as if you were having your first driving lessons, struggling to judge the radius of the corners. As a result, you’ll have to frequently readjust your line to avoid ending up too far inside or outside at the exit of the corner. However, after a while you’ll get used to it and you’ll be able to tell from the amount of resistance whether the handlebars are back in their central position. That being said, the steering behaviour isn’t as lively and, above all, requires noticeably more effort when snaking through fast, consecutive corners.

When riding in a straight line, the steering feels more stable, allowing you to loosen your grip on the bars slightly, especially in rough high-speed sections – provided you trust the system and the conditions are right. As a result, the bike inspires more confidence and lets you relax your body. The strong centring force becomes particularly evident with sudden steering manoeuvres, for example when you slip on a wet root and have to intervene spontaneously. This gives you a little more feedback on how the bike is moving underneath you.

Will the K.I.S revolutionise mountain biking?

Canyon claim that the K.I.S. brings several advantages to the trail. But is Syntace’s steering stabilisation system really that big of a revolution? Undoubtedly, it improves stability, albeit only when riding in a straight line and with smaller impacts. Consequently, we can see the K.I.S. being a good feature for gravel bikes, which are designed primarily for fast, uneven terrain but don’t have to deal with the challenging technical features typical of mountain bike trails, like nasty rock gardens, big compressions and big drops. The narrow handlebars of gravel bikes have less leverage, resulting in a twitchier front end, so installing a stabilisation system like the K.I.S. could be a real improvement, taking care of smaller unwanted steering movements.

But since the spring force decreases in corners and the system is too weak to compensate for bigger impacts on challenging trails with technical features such as rock gardens and root carpets, the K.I.S. system only benefits mountain bikers to some extent and in certain situations. However, there are other ways to achieve a similar effect, for example using more robust tires, which allow you to run lower air pressures, thus ensuring better damping qualities and more traction while at the same time protecting the rims from impacts. In addition, the greater rotating mass improves stability at high speeds.

On trails with fast and rough straight sections, the Keep It Stable system can reduce fatigue, simply because you don’t have to hold onto the grips as hard. However, it takes some time before you get used to the system and feel confident enough to relax on the bike. On top of that, the advantages are only marginal on rougher trails and with spontaneous direction changes. And there’s one more thing: the resistance requires you to work harder and makes you feel as if you’re working against the system rather than benefiting from it.

When looking at the bike in isolation, K.I.S. can theoretically prevent understeer. The fork is connected to the rear end via a spring, which exerts a force on the swingarm when tensioned, thus pulling the rear end into the same line of the front. In real life, however, we have to consider the overall system of the bike and rider. The force exerted by the rider via their body – which also connects the front to the rear – is far greater than that force of the spring itself. As a result, weighting the front is still the most effective way to prevent understeer.

When hydraulic disc brakes and dropper seat posts were first introduced to mountain biking, most of us were no longer able to imagine riding an MTB without them. Their positive impact was far too evident and raised the development of bikes to a whole new level, ultimately making mountain biking a lot safer. In our opinion, claiming that the K.I.S system will have a similar impact on the future of mountain biking is far-fetched, simply because the advantages it brings on the trail aren’t revolution-worthy.

Our conclusions about the K.I.S. system

Keep It Stable is an exciting invention that has a noticeable influence on the handling of a bike – both in a good and bad way. K.I.S. plays out its strengths on fast, straight trail sections, where it noticeably stabilises the handlebars, thus helping reduce fatigue on this type of trail. On technical terrain with fast, consecutive corners and spontaneous direction changes, you feel as if you were working against the system rather than benefiting from it and the bike feels slower and less nimble.